IN MY earliest memory of Mom she is talking with the milkman. Back in the day – early to mid- sixties — the Ewald Bros. milk truck came down Wilford Way once or more times a week. Stopping at our house, the milkman would dutifully carry our order up a lot of steps on the side hill up to the second story kitchen. Normally he’d put our goods in the corrugated tin box by the door and be on his way, but this day Mom caught him and found a willing conversational partner. The milkman stood in the threshold as Mom and he chatted, and talked, and discussed. I don’t recall any of their conversation, but it went on so long that I, developing my penchant for anxiety, worried that Mom would make the milkman late for his appointed rounds.

Mom loved talking. I don’t know how she wound up with such a taciturn kid as me, but there you go. Mom would look for settings conducive to conversation. The Wednesday night bridge club went on for years, where the ladies of the card table could freely chat. She was in a bowling league, also for years (team name: Wil-Ways), I’m sure more for the social comradery than the chance to beat the ladies from Dunberry Lane. And often, after Dad got home from work, the two of them would sit in the living room, in their matching chairs on either side of the antique serving table, discussing whatever there was to discuss, the room filling with cigarette smoke.

During the time I knew her, Mom was a suburban mom, with all that entails, but she confounded the stereotype. I think she found Edina a little stifling, and kind of funny. I don’t remember the source, but she cut out and kept a satirical poem about living in Edina (“with your living room window looking into mine…”). She had a good perspective about her place, and threw herself wholly into what suburban life afforded her. She was well-liked by all the other housewives on Wilford Way.

She never had a job, but she was always working. Laundry, cleaning, ironing. Making the beds, nice and tight. Putting Gold Bond and S&H stamps in the booklets. Bowling team captain, bowling league secretary. Making crafts (some still decorate our tree at Christmas). Once all us kids were in school, she did more outside of home: Working at the Blue Goose Auxiliary (I never really knew what that was), volunteering at the Abbott Hospital gift shop. Helping at the Reidhead’s Hallmark store in DinkyTown. She was exuberant about it all.

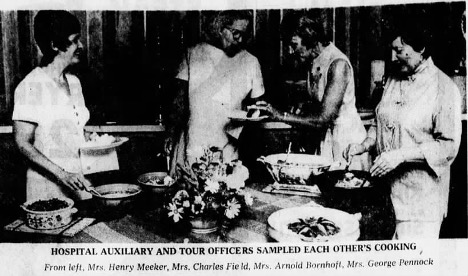

There’s a photo published in the Taste section of the Minneapolis Star in 1970, captioned “Hospital Auxiliary and Tour Officers Sampled Each Other’s Cooking.” It illustrates an article on the 10th Annual Abbott Kitchen Tour. The photo shows Mom (”Mrs. Arnold Bornhoft”) and three other women at a table filled with serving dishes and platters of food. Mom makes the photo worth publishing. She’s intently and joyfully serving one of the women a serving of some dish. The other women in the photo are smiling, but a little stiff.

Mom hated getting old. She actively hated it. I remember handmade “Life Begins at Forty” signs at the house, for a neighborhood party she hosted to celebrate that dreaded birthday. More than once she would lament, “Youth is wasted on the young,” as she looked at her boys lounging in front of the TV.

When I was in first grade Dad bought a cabin on a lake outside Siren, Wisconsin, and it became Mom’s favorite place to be.

She did what she could to make every day at “the lake place” a sunny day. She christened our tree fort “Fort Sunny,” the name spelled out in tree twigs on the side. She would look up at a cloudy sky and say, “I think it’s getting brighter.”

I picture her on the boat, fishing, anticipating the thrill of the catch. And sitting on the deck, containers of geraniums (her favorite) all around, at the end of the day.

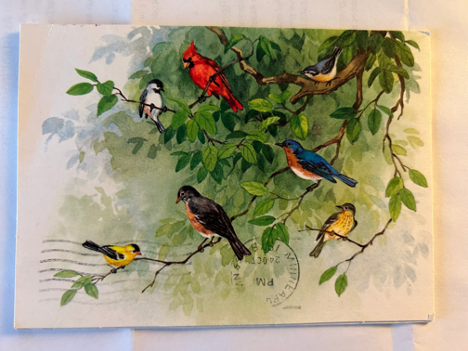

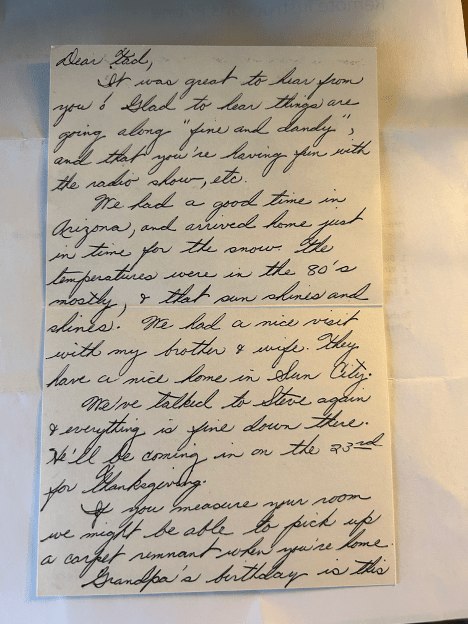

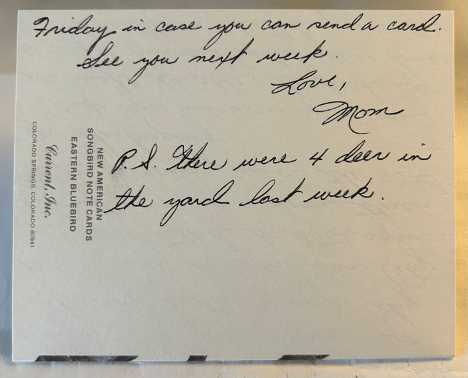

Mom loved songbirds. Whether this started with life at the cabin or before I don’t know, but it was one of the biggest interests of her life. She was ecstatic when we spotted a scarlet tanager at the lake place. She loved when the phoebes came back to the nest above the door every year. She once had a chance to meet Roger Tory Peterson, a noted ornithologist and nature artist; for her it was meeting a rock star. Her collection of ceramic bird sculptures kept growing until a cabinet was purchased just for their display. Notecards she sent to me at college always, always featured songbirds.

Like many things that seem to go on forever, we only had the cabin a short number of years. By the time I was in seventh grade Dad had sold it. We moved from Edina to a wooded acre lot in (Prestigious West) Bloomington, mostly to satisfy Mom’s love for the outdoors.

Mom loved to read. I’m sure it was a way for her to escape her suburban setting. I remember her reading books by Lowell Thomas, a foreign correspondent and travel writer. And like many women I think she was inspired by the essays of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, widow of Charles.

_________________

On a day in March of my junior year at Gustavus Adolphus College, the chaplin left a message for me to come to his office. Obviously something was up. I figured it might be about Dad’s stepdad, Grandpa Bill, who had various health issues. Mark and Jan were living in Minneapolis, Steve I think was in Madison, Wisconsin. Mom and Dad were vacationing in Mazatlán, using a condo in the Reidhead family.

I was nervous as I sat down in Chaplin Elvee’s office. “Your mother died last night in Mexico,” he said, directly but calmly. He remained quiet for a minute while I took it in.

Mom was 51 years old. Dad later told us she had collapsed while they were walking on the beach. After Dad asked someone to get help, he knelt by Mom. Mom, conscious but unable to talk, looking at Dad, took off her wedding ring, and put it in Dad’s hand.

Kim wears that ring now. The ceramic sun that hangs on our front porch was purchased by Mom in Mazatlán.

Grandpa Bill had picked me up from Gustavus. When I got home and went up to my room, my bankbook was on my desk, where Mom always put it after she’d made a deposit for me. She had washed my sheets since I’d last been home, and had made my bed, neatly and tightly, like she always did.